With over 20 years in the aerospace and defense industry, I am often amazed at the technologies embedded in the equipment used by our service members to defend our freedoms. Computing and connectivity are foundational to today's military operations. Most folks may not realize that almost none of the technologies we take for granted today existed during Operation Desert Storm. Desert Storm was America's last major conflict executed without the technologies currently part of today's connected battlespace. The lack of situational awareness caused confusion amongst U.S. forces and our allies, both in terms of friendly and opposing force locations, resulting in an unacceptably high rate of friendly fire and fratricide incidents.

In 1993, as a mid-career Captain fresh off a tour in Germany with the 11th Armored Calvary Regiment (ACR), I was assigned to the Dismounted Battlespace Battle Lab (DBBL) in Fort Benning, Georgia. I was confident, some might even say cocky, coming from one of the Army's most decorated units, having witnessed the fall of the Iron Curtain and the Soviet Bloc only a couple of years earlier. I was ready to take on the world. As an Armor Officer assigned to the "Home of the Infantry," I was one of a handful of Armor Captains selected to attend the Infantry Officer Advanced Course and subsequently completed both Ranger and Pathfinder schools.

Then, I commanded a Cavalry Troop along the former East/West German border, which shortly thereafter ceased to exist. My credentials well equipped me to fully understand that the Army needed to usher in a new warfighting strategy, one that would tie together sensors and shooters, provide real-time situational awareness, and significantly shorten the operations order processes bypassing orders digitally from Division to Platoon levels. This strategy was the beginning of the Rapid Force Projection Initiative and eventually led to Force XXI. Our team at the DBBL was about to develop the foundation of a new era of warfare.

Developing the Connected Battlespace

In this new assignment, as the project officer tasked with working with some of the Army's brightest minds (both military and civilian), our mission was to develop the Army's organizational, equipment, and tactical requirements that leveraged emerging networking and global positioning technologies. At the end of this initiative, we would demonstrate the warfighting capabilities of a properly equipped and organized Force XXI brigade. Our hypothesis was technology and a new organizational structure would result in expedited decision making, enhanced situational awareness, and significantly reduced fratricide rates.

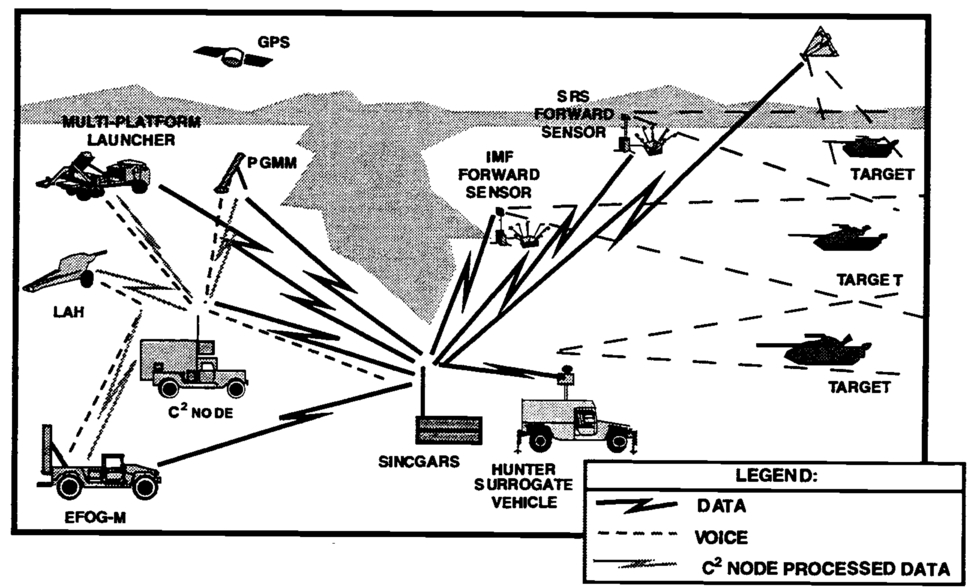

To make that happen, we discarded our "traditional" ways of thinking regarding warfare. From whitespace, we came up with the concepts, organizations, equipment, and battlespace connectivity necessary to achieve dominance over potential opposing forces operating under Cold War concepts, redefining almost every phase of operations. In the context of the new technologies, we studied every aspect of command and control, starting with communications. Before this initiative, tactical radio was the primary means of communications, used extensively in all phases, from issuing orders through combat operations.

In the heat of battle, radio communication becomes indiscernible and unworkable at times. The "Fog of War" quickly ensues, and the accompanying chaos takes over most radio frequencies, thus multiplying the confusion of determining and tracking both friendly and enemy locations. However, with the digital command and control technologies, both friendly and enemy locations were auto-populated based on GPS coordinates, and live intelligence feeds from our sensors.

Another problem solved by the advent of these new technologies was order dissemination. Prior to these digital technologies, plans were typed on a computer, printed on a dot-matrix printer, copied on archaic photocopiers, and then physically distributed along with an overlay drawn on acetate. That sequence was repeated at every level of command, taking dozens of hours and leaving the door open for human errors in copying. And, the time spent driving back and forth between command posts in the middle of the night was fraught with dangers. The advent of digitized technologies allowed orders to be sent instantly via a connected network of command posts, thus offering greatly enhanced accuracy, reduced copy errors, and saving hundreds of combined hours of commutes between command posts.

To make all of this work, the most crucial step in proving the value this technology provided was gaining the trust and confidence of the units we trained and equipped. We needed their buy-in, which came from understanding that digitization saved them time and tremendously enhanced their ability to shoot, move, and communicate while reducing fratricide.

Change, regardless of magnitude, almost always comes with resistance and its own set of challenges. To best understand these challenges, one must remember that other than the Soldiers and civilians working on this initiative, very few people understood these technologies or how they would revolutionize the Army's warfighting capabilities. These new technologies necessitated a change to virtually every standard operating procedure from platoon to division levels. It also drove significant changes in tactical and strategic concepts foundational in how the Army conducted warfare. The melding together of these warfighting concepts was key to our mission success.

Over two years, this talented team of battle lab professionals, working with some of the best and brightest defense contractors, took this from concept through to something known as an Advanced Concept Technology Demonstration (ACTD). This ACTD was a brigade-level proof-of-principle warfighter exercise held at Fort Drum, New York, and attended by the Secretary of Defense. That exercise went off flawlessly, but it was not the highlight of my career. More important to me was the continued work I was able to do in the development of the Force XXI as a tank battalion and brigade operations officer for the first digitized brigade outfitted with the technologies that I played a significant role in developing.

The Future Connected Battlespace

Today, these technologies are commonplace for our warfighters. In Operation Enduring Freedom, virtually every vehicle was equipped with the technologies conceived, tested, and matured in the Force XXI experiment. What started in the battle lab in 1993, the vision of a battlefield where every Soldier and vehicle equipped with a digitally connected sensor suite came to fruition in a splendid way. This suite of tools enabled every person and vehicle to serve as a mobile intelligence gathering instrument. Almost everything we envisioned in 1993 became a reality. Naturally, some other technologies matured during and after our initial concept. Perhaps the most important one was the significance of unmanned surveillance systems.

Even today, opportunities to better collect data on the environment surrounding our warfighters remain. The DOD still faces challenges in signal interception/detection, requirements to keep soldiers' equipment light and rugged, and controlling the costs of putting these technologies in the hands of our warfighters. We are striving to overcome these challenges to make our vision of the "future battlefield" a reality. However, new programs like the Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) provide Soldiers with data where and when they need it to optimize operational capabilities.

As a business development executive, I find it very rewarding to see our customer's programs continuing to drive enhancements within the connected battlespace. The work we do with defense industry leaders allows today's service members to overcome obstacles such as signal interception, SWaP limitations, and more. We are dedicated to our mission to provide our warfighters with the tools needed to enhance mission accomplishment and to provide better survivability well into the future.

Interested in learning more about Benchmark's defense system development capabilities? Read more here.